Technical Manual Chapter One

Ch 1: Introduction

This technical report describes research and development specific to the Virginia Language & Literacy Screening System (VALLSS) for Grades K-3, which assesses the English language and literacy skills of individual students during the early elementary school grades. VALLSS: Grades K-3 is one of several tests that form part of the screening system, which we describe below. VALLSS: Grades K-3 is required for all students in Grades K-2 and select Grade 3 students during assessment windows in the fall, mid-year, and spring.

Background

VALLSS was developed through a collaborative effort between the Virginia Department of Education (VDOE) and Virginia Literacy Partnerships (VLP). The screening system was created to provide students and educators with access to state-of-the-art tools in supporting reading success. For over 20 years and prior to VALLSS, scores from the Phonological Awareness Literacy Screening (PALS) were used to identify students with a risk for reading difficulty. Public-school educators in Grades K-3 within the state of Virginia relied on these PALS scores for identification of students at risk for reading difficulties and had access to resources for the interpretation and use of PALS during this time. There is a longstanding tradition of VLP support for educators in Virginia for literacy screening and intervention, and the development of VALLSS is an extension of the partnership between VDOE and researchers at the University of Virginia. Therefore, the design of VALLSS and the systems in place to support the use of VALLSS are best understood as efforts that build on the ongoing statewide practice of using student-level data to inform instructional decisions.

An introduction to VALLSS would be incomplete without mention of state policy. Just as the screener builds on the partnership between invested members of the research and local community over decades, recent policy builds on the work of legislators in years past. The Early Intervention Reading Initiative (EIRI) was established in 1997 to prevent the development of reading difficulties in the early grades. Legislators have extended EIRI in recent years. Legislators extended EIRI when they passed the Virginia Literacy Act (VLA) in 2022, which codified a number of state-wide changes that came into effect beginning with the 2024-25 academic year, among other initiatives. These policy changes address the resources available to students, families, teachers, and local education agencies. Statewide changes stipulated within the VLA include expectations about the curricula (core, supplemental, and intervention) that schools rely on to provide literacy instruction, revamped training for reading specialists, teachers, and administrators in the early grades, and a literacy screener to support the educational program of students who would benefit from targeted instruction (VALLSS). Legislation also provides funding for 2.5 hours of intervention above and beyond regular classroom instruction for each K-3 student at high risk for developing reading difficulties. Early identification is key to this policy; funding for VALLSS research and development was provided by a contract between the state of Virginia and Principal Investigators Drs. Emily Solari and James Soland. A complementary state report with additional background is available (link; semi-annual fall-spring).

System Overview

VLP has undertaken VALLSS research and development of both English and Spanish screeners for use in preschools and in elementary schools from kindergarten through third grade. While the current report focuses on VALLSS: Grades K-3, separate technical manuals for each of the following screeners (including this one) are expected:

-

VALLS: Pre-K

-

VALLS: Español Pre-K

-

VALLSS: Español K-3

-

VALLS: 4-8

The resources and timelines for the research and development of each of these tests vary. For example, the number and locations of students who are enrolled in preschool as three-year-olds or whose instruction includes Spanish literacy is much lower than those who are enrolled in elementary school when compulsory education begins and whose instruction includes English literacy. Therefore, the technical reports for each screener that is part of VALLSS will be released separately. Interested readers can also access Front Matter files for each of the screeners via the VLP website (click the Screener+ option from the menu). Because evidence for the use of newly developed instruments can build over time, we use versioning to periodically update each of these reports. Information is generally added and not removed when a report is updated.

Timelines

VALLSS development took place over several years, and continued research on reliability and fidelity is ongoing. VLP’s design of the screening system, a plan for the purpose and scope of each test, and the development of items took place between early 2019 and the summer of 2021. Phases of research and development include what we refer to as Pilot, Soft Launch, and statewide Launch. Development refers to activities such as data analytic design, project planning, and item writing; these activities rely the least on access to end users of the screener. Pilot and Soft Launch took development efforts into the field to trial screener items with students. Launch refers to test release for use in schools. Table 1 presents the years over which each of these phases took place, by test, for each screener that makes up VALLSS.

Table 1.

System-Wide Chronological Overview of Piloting, by Test

| VALLSS | 2019-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-K | Development | Pilot | VA Launch | R & D | R & D |

| Grades K-3 | Development | Pilot | Pilot | Soft Launch | VA Launch |

| Español K-3 | Development | Pilot | Pilot | Pilot | Soft Launch |

| Español Pre-K | Development | Pilot | Pilot | Pilot | Soft Launch |

Note. R & D = research and development.

VALLSS: Grades K-3. The Pilot years for VALLSS: K-3 ran from fall of 2021 through spring of 2023. These Pilot years yielded information about items’ functioning and students’ interactions during screener administration. Next, during the 2023-2024 Soft Launch, items were selected for more widespread administration within three assessment windows, which take place during the fall, mid-year (January), and spring of an academic year. VLP also undertook additional piloting efforts during the same year to calibrate data on additional code-based items for each assessment window, gather information on additional oral reading fluency passages for progress monitoring, and build on the available language comprehension passages. Soft Launch efforts yielded data from over 60,000 students. The information from the Soft Launch was in turn used in psychometric analyses aligned with the intended uses of the K-3 screener. VALLSS content was verified or updated based on that work, resulting in the content released during the statewide Launch in the fall of 2024. (Psychometric methods and properties of the test are described shortly.)

Rationale

The decision to develop a new screener was based in part on the feasibility of applying advances in the fields of psychometrics and reading on a large scale. Advanced measurement methods and the increasing use of technology in schools have resulted in the advent of computer-based testing. All of these technologies in combination make it a realistic option to provide detailed, real-time, student-level literacy assessment results to practitioners within an educational setting. For example, psychometric approaches such as vertical scaling (Briggs & Weeks, 2009) ensure that an instrument is sensitive to change over time, and that a score at one point in time is comparable to a score from a different point in time. Vertical scaling is therefore an apt approach for modeling literacy growth to help determine whether and what type of instructional changes are needed during the course of a school year. Private developers have wielded more and more advanced psychometric methods and eventually the power of computer software to develop computer administered and even adaptive screeners (see Curriculum Associates, 2014 and 2018 and Northwest Evaluation Association, 2011 and 2019 for noteworthy examples). Recall that PALS was released in Virginia in 2000. So, while some of the advances we apply have been available for decades, schools in Virginia before VLA did not yet have free access to scores that rely on these methods. VALLSS: K-3 was therefore conceptualized as a way to increase trustworthiness of literacy assessment by providing educators in the Commonwealth with scores deemed psychometrically sound for the purposes of screening and instructional decisions, all while providing results almost instantly via digital interface.

As for advances in the science of reading, VALLSS measures skills that are widely understood to be proximal to and support long-term development of literacy. VLP researchers applied the simple view of reading (SVR, Gough & Tunmer, 1986), which is an empirically validated framework that stipulates that both code-based (e.g., phonological awareness, alphabet knowledge, alphabetic principle, phonics) and language comprehension skills (e.g., vocabulary, semantics, linguistic knowledge) are requisite components for the development of reading comprehension. While SVR is not a recent development, measurement of both language and code-based skills in universal literacy assessment is not yet common at a large scale. As with psychometric advances, widespread access to computers within schools has made more efficient assessment and scoring of skills like language comprehension tenable. Students with lower levels of oral language (i.e., the skills and knowledge that support listening and speaking) may also experience challenges with reading comprehension (e.g., Catts et al., 2006; Justice et al., 2013). As such, it is critical to assess oral language early and often, and to facilitate the language skills that support reading comprehension (e.g., Adlof & Hogan, 2019; LARRC, 2017). Foundational literacy skills identified through the SVR and by national panels [e.g., National Reading Panel (NRP), 2000] have also since been implicated in later oral reading fluency and reading achievement (Clemens et al., 2011, Goffreda et al., 2009). Therefore, in addition to measuring language, VALLSS: K-3 was developed to build on PALS by addressing skills such as encoding and decoding. Finally, findings from fields addressing science-based reading research have converged over the past several decades to describe how the brain processes written language and develops literacy. Based on these advances, VLP has developed VALLSS, which measures related constructs implicated in literacy development, such as code-based, language comprehension, and processing skills. These constructs anchor measurement throughout VALLSS. Evidence presented through this report addresses the subtests developed to measure these constructs within Grades K to 3 and the interpretation of the resulting VALLSS scores. This evidence is presented within a validation framework.

Validation Framework

The validity of a measure is the trustworthiness and the meaningfulness of the ways the scores are interpreted and used (AERA et al., 2014). In this manual, we use the interpretation and use argument (IUA) approach to validation (Kane, 2013), in which claims about the meaning and uses of the scores produced by a measurement instrument are supported by empirical evidence. Said differently, validity is not a property of a measure; it is inextricably linked to the intended uses of scores, including who is being measured. Validity arguments are therefore an iterative, ongoing presentation of evidence that claims about how scores will be used are justifiable. These claims stem from a series of inferences that can be made about the scores. In an IUA, the assumptions underlying each inference are made explicit and are empirically tested.

Kane (2013) described at least three types of inferences that could be made: scoring, generalization, and extrapolation. Scoring inferences are associated with claims about the technical quality of the scores produced by a measurement instrument and how accurately those scores represent the construct of interest. Generalization inferences are concerned with the relationship between tested and untested content. For any given construct, there is a hypothetical universe of relevant content from which test developers can sample items. For scores on a measurement instrument to be generalizable, the resulting scores should be similar to those that would have been obtained had a different sample of items been selected from that universe. Finally, extrapolation inferences connect scores with the larger domain represented by the measured construct. These types of inferences explore whether a student who obtains a high score on a test is able to apply their knowledge in a different context.

In the chapters that follow, we articulate our claims about the scores produced by VALLSS and how they will be used and provide empirical evidence to support our inferences. Given that these inferences are inextricably linked to the purpose and the intended uses of VALLSS, we first outline the constructs that VALLSS was designed to measure and the ways the resulting scores are meant to be used by various stakeholders.

Test Content and Purpose

Because reading relies on complex processes, VALLSS uses multiple subtests to measure skills that are widely understood to support development of literacy long-term. Each subtest primarily measures either a code-based literacy or language comprehension skill, or processing. Subtests sometimes represent constructs in their own right. Oftentimes, these subtests merely represent particular clusters of skills within a unidimensional construct. For example, the code-based construct includes the alphabetic knowledge skill, which is measured through the Letter Names and Letter Sounds subtests. Other subtests represent skills largely unique from those clustered under a specific construct, an example of which is the Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) subtest. VALLSS subtests are nonetheless organized under the three broadest constructs aligned with current research on early predictive skills of later reading ability. The same three constructs are represented in every grade, though the makeup of subtests used to measure each construct occasionally differs across grade or even assessment term. Any such differences in how VALLSS measures code-based skills rely on appropriate psychometric modeling and reflect the developmental nature of literacy learning over time.

Intended uses of VALLSS

The screening system is meant to serve students, teachers, and families in Grades Pre-K to Grade 3 across Virginia. VALLSS: Grades K-3 is used to assess every student enrolled in Grades K, 1, or 2 in any public school within the state of Virginia. Students in Grade 3 must be assessed if they were designated as high-risk in the spring of Grade 2 on VALLSS, received summer intervention services, or are new to Virginia public schools.

The scores from VALLSS: Grades K-3 are to be used for three main purposes. First, scores designate which students will receive early intervention. Through the assessment of code-based English literacy skills, each student is classified at each assessment term based on their risk for developing a reading difficulty within that term (i.e., fall, mid-year, or spring). This risk classification, or Band of Risk (BOR), summarizes information about code-based skills so that stakeholders can make decisions about the best way to support the development of each students’ literacy. Each student’s scaled score indicates either a low-risk, moderate-risk, or high-risk BOR. VALLSS relies on these three levels of classification in an effort to discourage the interpretation of risk as a student characteristic and encourage more nuanced score interpretation and use. The goal is to support targeted instruction, which can be enhanced with information about which students are most at risk for developing reading difficulty. This BOR is updated via periodic assessment, so it is to be used for decisions about the intensity (i.e., time, group size) of instruction in the short-term. Per EIRI legislation, every student in the high-risk BOR in Grades K through 3 is provided access to 2.5 additional targeted early reading instruction hours per week.

A second purpose for using VALLSS is the identification of target skills for intervention and support. Subtests from VALLSS provide information about each students’ performance across an array of instructionally relevant foundational skills. VALLSS scores include an indicator, hereafter referred to as the Instructional Indicator, for every subtest. These Instructional Indicators differentiate specific skill areas of in need of additional explicit instruction. The intended use of these Instructional Indicators is to identify the skills educators can target during literacy instruction. The only exception is the processing Rapid Automatized Naming: Letters (RAN) subtest, for which the indicator is not tied to instruction.

Finally, scores can be used to monitor literacy development over time. The development of VALLSS subtests that go into BOR included measurement methods that will typically make the comparison of a students’ scaled score at one point in time to their scaled score at another point in time appropriate.

Limitations

VALLSS student-level data can be used to make decisions about the degree of early intervention support appropriate for a student at a given time, the skills that could be targeted during literacy instruction (through Instructional Indicators), and the extent to which a student’s code-based skills have changed after a period of instruction. No additional uses for student-level scores are intended, and any use of aggregate scores should be carefully considered.

VALLSS: Grades K-3 is first and foremost an early literacy screener. VALLSS differs from an end-of-unit assessment or assessment of mastery. Educators interested in understanding literacy skills relative to certain end-of-unit, curricular, or other summative criteria should rely on assessments designed for such uses. While VALLSS was designed to support instructional decisions with respect to dosage and content, the screener cannot be used in place of other tools in a diagnostic evaluation nor for the identification of a disability for school purposes.

Subtests

VALLSS is comprised of multiple subtests. VALLSS subtests were selected to align with at least one of the aforementioned constructs: processing, language, or reading. The VLP team further identified subtests for VALLSS: Grades K-3 that provide a foundation for the three intended uses of scores (i.e., determining which students receive intervention services, identifying skills which need to be targeted, and monitoring student literacy growth). As such, VALLSS emphasizes subtests that measure instructionally actionable literacy skills. Each subtest score has a nearly direct instructional application, with one exception: RAN. This subtest was retained because of persistent historical evidence of its predictive utility, and not for its instructional application.

We next describe each of the code-based, language-based, and processing subtests that form the English VALLSS: Grades K-3. All subtests are standardized, have scripted instructions, and are administered by an educator with access to VALLSS-specific training. Unless otherwise stated, administration is one-on-one. Responses for each item are recorded on a computer. See Table 2 for an overview of the grades within which each required subtest is administered.

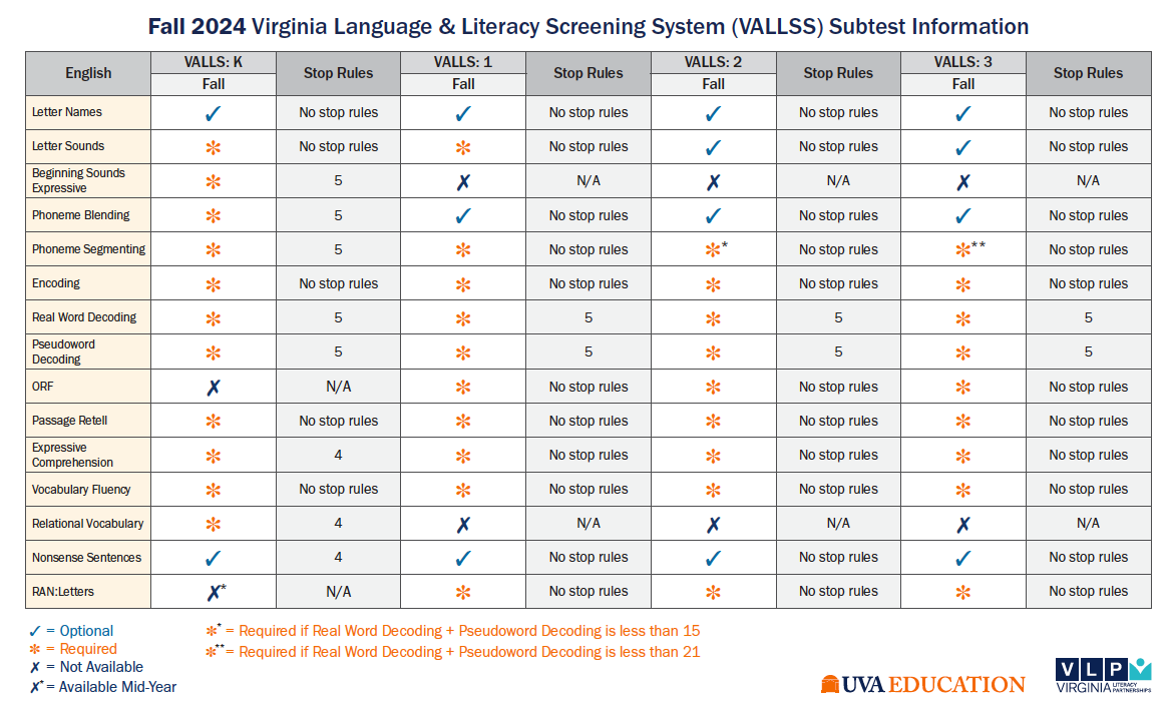

Table 2.

VALLSS: Grades K-3 Subtests: Fall 2024

Code-Based Subtests

Code-based VALLSS subtests include reading fluency and early literacy subtests common in the measurement of phonological skills, as well as oral and written demonstrations of understanding sub-word- and word-level alphabetic principle. ORF is the only timed code-based subtest. Unless otherwise stated, the number of items varies across assessment term (i.e., fall, mid-year, and spring), and item scoring is done on the computer.

Letter Names. Students are given a page that depicts both the uppercase and lowercase form of each letter of the alphabet in random order. Each of the 26 letters in the English alphabet is therefore presented twice for a total of 52 items. Students are asked to state the name of each printed letter. Items are scored correct for each letter named accurately and in order from left to right and top of the page to the bottom.

Letter Sounds. Students are given a page that depicts each letter of the alphabet in random order. Each letter appears as a pair (i.e., both uppercase and lowercase together). In addition to each letter from the alphabet, three common digraphs are included: th, sh, and ch. For each item (a letter pair or digraph), students are asked to produce the sound for a letter (e.g., /d/ for “Dd”). An item is scored correct if the student accurately produces the letter sound. One practice item, “Mm” with the letter sound /m/, is provided with corrective feedback. Differences due to dialectical differences are not penalized.

Beginning Sounds Expressive. For each item, students hear a target word read aloud and are asked to give the initial sound of the word or a word beginning with the same sound as the target word. Two practice items with corrective feedback and heavy prompting are provided prior to beginning the assessment. Each item is scored correct if the student accurately produces the initial sound alone or provides a word with the same beginning sound.

Phoneme Blending. For each item, students are presented with a series of individual sounds and are asked to blend them to produce the whole target word. Two practice items with corrective feedback and heavy prompting are provided prior to beginning the subtest. An item is scored correct if the student blends the word accurately and smoothly (i.e., without a pause between sounds).

Segmenting Phonemes. For each item, the students listen to the target word out loud. Students divide the word into individual phonemes (i.e., component sounds). Two practice items with corrective feedback and heavy prompting are provided prior to beginning the assessment. An item is scored correct if the student accurately produces each individual sound within the word, in order, with a clear pause between each sound.

Real Word Decoding. Students are given a page with a list of real, decodable words to read. Each item (one word) is marked correct if read accurately and smoothly.

Pseudoword Decoding. Students are given a page with a list of made up, decodable words to read. Each of the pseudowords is not a real word. Each item (one pseudoword) is marked correct if read smoothly and accurately according to typical decodable spelling patterns.

Encoding. Students are given a sheet of paper and asked to spell words that are read to them aloud. Letter reversals are accepted as correct. The way the student spells each word is entered into the computer. Each item (a word) that is spelled correctly is marked “all correct” and given full credit. For each item with an incorrect spelling, a letter sequence algorithm is used to determine any partial credit. This subtest can be administered in a group setting, where each student silently writes on their own sheet of paper while the words are read aloud to the group.

ORF. Students are given a piece of paper with a passage and asked to read aloud. Words that are skipped or misread are marked incorrect on the computer while the student reads. Students are given one minute to read from the passage, and the score for this subtest is the total number of words read correctly during that time. Self-corrections are counted as words read correctly.

Language Comprehension Subtests

VALLSS Language Comprehension subtests include both expressive and receptive language skills common in the measurement of language comprehension. These subtests measure language in the areas of form (e.g., syntax, morphology), content (e.g., vocabulary), and use (e.g., organizing ideas using a logical flow). The vocabulary fluency subtest is the only timed language comprehension subtest. The number of items on some subtests vary across assessment term (i.e., fall and spring). Additionally, unless otherwise stated, scoring occurs on the computer.

Passage Retell. Students listen to a passage read aloud by the test administrator and view accompanying illustrations. Then, the student is asked to retell the passage using the same set of illustrations. The test administrator uses a rubric to score the retell and assigns either full, partial, or no credit for each rubric item. Six items aligned to fiction and narrative non-fiction accompany those passages, while five items aligned to expository (non-fiction) accompany those passages. Three items included in all rubrics ask about the following features: the richness and sophistication of vocabulary, the extent to which the student uses complete sentences, and how well the retell makes sense as a whole. Fiction and narrative non-fiction passage rubrics include items that ask about how the student describes the character(s)/setting, includes key details, and includes expressive elements (e.g., dialogue, onomatopoeia). By contrast, expository passage rubric items ask about how the student conveys facts from the passage and includes cause and effect wording.

Passage Comprehension Questions. This subtest is administered immediately after Passage Retell. The test administrator reads aloud a series of expressive comprehension questions, one at a time, about the same passage. For each item, the student responds orally to a question. The administrator uses a rubric to score student responses, assigning either full, partial, or no credit for each item.

Vocabulary Fluency. Students are presented with a series of individual color illustrations depicting common objects and concepts. For each item, the student must accurately name the word depicted. Items for which students produce a more sophisticated or specific version of the target word (i.e., barbell for weight) are also scored correct. This is a timed subtest; the score is the total correct in one minute.

Relational Vocabulary. For each item, students view a grid containing four simple illustrations depicting the relationship between a box and a ball while listening to a sentence read aloud (e.g., “The ball is over the box.”). Students must identify the one picture, out of the four options, that matches the target relational vocabulary word. In this receptive task, students indicate their response by touching the picture they believe best matches the target. Each item is marked correct if the student accurately identifies the target picture.

Nonsense Sentences. Students listen to one sentence at a time read aloud by a computer. The sentences are nonsensical in meaning, but follow correct grammatical conventions (e.g., The doctor checked my arm because I like elephants.). For each item, students are asked to repeat the target sentence to the test administrator. Two practice items with corrective feedback and heavy prompting are provided prior to beginning the assessment. An item is scored correct if the student accurately repeats the sentence exactly as it was read.

Processing Subtest

RAN. Students are presented with a piece of paper that has an array of 50 letters, listed 10 letters per row. The same five letters are repeated, in random order. Students are asked to name the letters as quickly as possible. This is a timed subtest. Students are given one minute to name as many of the letters as possible, and the score for this subtest is the number of letters labeled correctly during that time. Self-corrections are counted as letters read correctly.

The process for determining the scope of content covered by each subtest is described in further detail in Chapter 2; evidence about the technical adequacy of items developed for these subtests is presented in Chapter 3.

DRAFT V1 (February, 2025)